by Scott McDermott

Guest Blogger

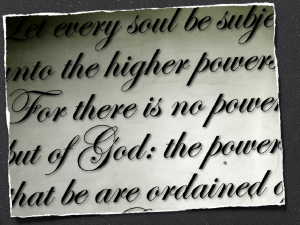

The Massachusetts Body of Liberties, 1641.

The Founding Fathers based the

American republic on the concepts of natural law, natural rights, popular

sovereignty, corporatism, the moral economy, and the right of resistance to

tyranny. All of these concepts derived

from Catholic political thought of the Middle Ages. But how did the Protestant Founders,

anti-Catholic to a man, come by these ideas?

In my book

Charles Carroll of Carrollton: Faithful Revolutionary,

I suggested that Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of

Independence, served as a vector of Catholic political concepts during the

American founding. But Carroll, however

influential, was only one man. And the

thesis of Carroll's influence falls afoul of the objection that also thwarts

the usual scholarly explanation, that Catholic political ideas came to America

mediated and distorted through Enlightenment writings. But if Enlightened thinkers transmitted these

ideas, how did they become embedded in colonial political culture

long before the

Enlightenment reached these shores?

My

recent research suggests a most unlikely conduit for Catholic political

teaching in the American colonies:

Puritans educated in the tradition of Protestant scholasticism. Although Martin Luther famously rejected

scholastic learning, important early Reformers like

Theodore Beza and

Philipp Melanchthon understood

that Protestants would need scholastic tools in order to debate effectively

against Catholic apologists. Thus,

Protestant universities and academies retained the seven liberal arts and the

“three philosophies” -- metaphysics, natural philosophy, and moral philosophy

-- as the bedrock of their undergraduate curricula. While the theology course changed

drastically, theology was a graduate program, and most ministers in the English-speaking

world took up their posts possessing only a B.A. degree that rested on the

traditional Aristotelian learning of the Middle Ages. Their formation in political thought, taught

under the rubric of moral philosophy, derived from two textbooks, Aristotle's

Politics

and

Nicomachean Ethics, and such commentators on those works as Thomas

Aquinas and "

The Schoolmen," a tradition known as scholasticism.

The

chief bastion of Protestant scholasticism in England was Emmanuel College,

Cambridge. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison has shown that thirty-five former students at Emmanuel migrated to New England between

1630 and 1640. Of the “Emmanuel 35,”

eight spent time living in the village of Ipswich, Massachusetts. This group of men, who formed the nucleus of

what I call the “Ipswich Connection,” included some of the colony's most

important political leaders and constituted the main opposition to the policies

of Governor John Winthrop. Simon

Bradstreet served as the colony's governor; so did his father-in-law Thomas

Dudley. Emmanuel men Richard Saltonstall

and Daniel Denison also became part of Massachusetts' elite ruling class. But the

linchpin of the Ipswich Connection was Nathaniel Ward, a minister,

lawyer, and prolific author who took his B.A. in 1600 and his M.A. in 1603 from Emmanuel.

Nathaniel

Ward was the principal author of Massachusetts Bay's first law code,

the Body of Liberties of 1641, passed over Winthrop's strenuous objections. Other members of the Ipswich Connection

supported the code enthusiastically. The

Body of Liberties reveals at every turn the scholastic political formation of

its Ipswich backers, beginning with its title, which derives from the

scholastic doctrine of corporatism, the metaphor of society as a body combined

with the belief that political communities have a real and autonomous

existence. Indeed, Ward divided his

document into sections devoted to different corporate groups in society, namely

freemen, women, children, servants, “Forreiners and Strangers,” the churches,

and even domestic animals.

Natural

law and natural rights appear in the very first Liberty, which protected life,

liberty, and property:

No mans life shall be taken away,

no mans honour or good name shall be stayned, no mans person shall be arested,

restrayned, banished, dismembred, nor any wayes punished, no man shall be

deprived of his wife or his children, no mans goods shall be taken away from

him, nor any way indammaged...unlesse it be by vertue or equitie of some

expresse law of the Country waranting the same...or in case of the defect of a

law in any parteculer case by the word of god.

Numerous other liberties defined

due process of law, while Liberties 45 and 46 restricted the use of torture and

prohibited “inhumane Barbarous or cruel” punishment.

In

keeping with Catholic principles of moral economy, the Liberties banned

monopolies, provided for grazing rights on common lands, protected common

fishing and fowling rights, and prohibited “any usurie amongst us contrarie to

the law of god” (although an 8% penalty was permitted on overdue debts). The Preamble upheld the principle of popular

sovereignty by declaring that “We...ratify them [the Liberties] with our

sollemne consent,” while Liberty 98 defined the procedure for ratification by

the people. The Body of Liberties aimed

to produce a well-regulated body politic in which arbitrary government (of the

sort the Ipswich men believed Winthrop was exercising) would become impossible,

not only because the government had to respect the legitimate rights of

different orders in society, but because it protected the freemen's privilege

of political participation. The

Liberties do not explicitly invoke the right of resistance to tyranny, but the

dogged opposition by the Ipswich Connection to Winthrop embodies it.

For all these reasons,

the 1641 Body of Liberties provides a touchstone for those who seek the point when Catholic Scholastic political concepts entered the American body politic.

Scott McDermott has a Ph.D. in American History from Saint Louis University and is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Tusculum College in Greeneville, Tennessee.